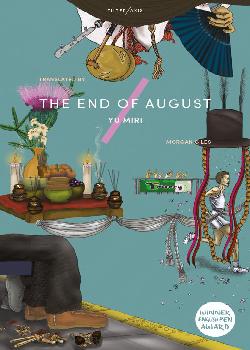

The End of August

By Yu Miri

Translated by Morgan Giles

Tilted Axis Press (2023)

ISBN-13: 978-1911284697

Review by Laurence Green

How does one go about piecing together the minutiae of generational trauma? To unpick and unpack the heavy theme of postwar migration of Koreans to Japan in novel form, without appearing trite or superficial? If anyone is up to the challenge, then surely it is Yu Miri, whose Tokyo Ueno Station was a razor-like intervention into the much-overlooked theme of homelessness in Japan. Unafraid to tackle arguably taboo themes, Yu was well-deservedly rewarded when Morgan Giles’ deft translation of Tokyo Ueno Station picked up a National Book Award in 2020, simultaneously prompting renewed interest in the book back in Japan.

In The End of August - originally released in 2004 in Japanese, but appearing for the first time in English translation, again from Morgan Giles - Yu turns the lens on another complex, intimidating topic. Taking as its setting 1930s Japanese-occupied Korea, the plot centres around star runner Lee Woo-Cheol, who - in what is a deft bit of blurring between auto-fiction and reality - is the grandfather of Yu Miri.. The novel plays out as a complex familial web of relatives and acquaintances, past and present intermixed and interwoven in much the same manner as the fraught relations between Japan and Korea are exposed through characters such as a young teenager who is tricked into becoming a comfort woman for Japanese soldiers. Yu is present within the story as both potential authorial self-insert and character in her own right.

Touted as a semi-autobiographical dissection of nationhood and family, the novel goes to great pains to cut deep into the minefield of identity as comprised of what we are born into, and what is imposed on us. Yu’s authorial voice is sharp and modern in its approach, mixing in a constant breath-like refrain of inhalation and exhalation (the ever-present rhythm of the runner), whilst simultaneously feeling in debt to classic familial sagas like Tanizaki’s The Makioka Sisters. The result is a work that feels like a totem of high literary ‘art’ - impossible to consume as a straightforward narrative, but rather as a series of interlinked experiments; pen-portraits that need to be chewed over, savoured, and analysed in minutely slow page-by-page detail to extract maximum value.

What fascinates about Miri is her multifacetedness as a writer. The now sadly out of print Gold Rush saw her operating with a literary tone and pace that felt more akin to a crime thriller author, while some of the best moments of the aforementioned Tokyo Ueno Station felt like the script to a primetime TV documentary. The End of August feels like something else again; so lyrically (and sometimes quite literally textually) bold in places - with many passages of Korean language left largely untranslated in this English version - and yet offering a tale that is ultimately about the most essential of human drives and desires. The novel feels intimately wrapped up in a zone of consciousness in which nation and body are inseparable - sex, language, blood, birth - all become an inseparable tangle of thoughtspace in which identity - Korean, Japanese, both, neither - become questions that require the space of 700 pages worth of textual disassemblage to get even halfway closer to answering.

The End of August stands as both a supreme literary accomplishment, and supreme literary challenge. Its intimidating length and style will prove insurmountable for many - while for those with the patience to work at it, excavating its rewards piece by piece, the lyrical beauty at its heart will begin to shine through. For those new to Yu’s writing, this is resolutely not a great entry point - but make no doubt about it, this hefty tome is another landmark entry in the career of one of Japan’s most important contemporary voices, and the sheer accomplishment of its translation into English is an impressive statement of intent in allowing that voice to shine through to the widest possible audience.