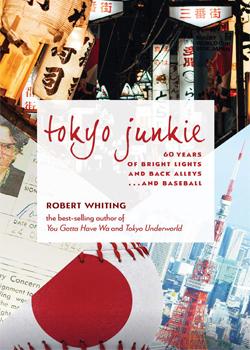

Tokyo Junkie: 60 Years of Bright Lights and Back Alleys... and Baseball

By Robert Whiting

Stone Bridge Press (2021)

ISBN-13: 978-1611720679

Review by Laurence Green

Time has a way of getting to you. Half a century is a good spell of time, by anyone’s measure. For Robert Whiting, a journalist and author who has lived in Tokyo on and off for more than fifty years, looking back over that vast spread of years comes in the form of a fascinating memoir - Tokyo Junkie - that plays out like a love letter to what Anthony Bourdain dubbed, ‘the greatest city in the world’. Beginning as a series of articles for the Japan Times back in 2014, Whiting - whose previous books You Gotta Have Wa and Tokyo Underworld have also become Japanese best-sellers in their translated versions - has an ambitious task at hand with this expansive volume, interweaving his personal narrative into the unfolding backdrop of Japan’s own great journey through time.

How does one set about capturing such scale? It helps to have a raconteur-like knack for good, old-fashioned storytelling, and with Tokyo Junkie, the tone is invariably brusque, to-the-point, straight talking. Whiting tells it like it was - and the account is all the more engrossing for its candid nature, even if at times its sprawling trajectory threatens to lose us halfway between national history and anecdote. Japan's journey from postwar devastation to the pinnacle of urban modernity is well told, but it's the personal touches that linger most in the memory. As Whiting openly admits, many will come across as shocking or striking to modern readers, but are included by way of holding up a lens of accuracy to the times in which they occurred. As the famous LP Hartley quote goes: ‘The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there’.

Hailing from rural California, and originally assigned to Tokyo as part of the United States Air Force, Whiting and his memoirs are initially presented through the lens of America’s postwar military involvement in Japan; the scope, however, quickly becomes more expansive. One of Whiting's acquaintances in the early 60s is an eminent plastic surgeon in need of an English tutor. Whiting is happy to oblige. One of Japan's '1%', the surgeon has a lucrative line in 'augmenting' nightclub hostesses looking to 'enhance their professional appeal'. Later, at the surgeon's luxurious new Harajuku apartment, they sip Napoleon brandy, watching Tokyo's 1964 Olympic opening ceremony, in the company of two movie actresses 'wearing trendy Mary Quant miniskirts'. Japan's return to the world stage is complete.

These early passages are richly evocative of a world of sex, sultry nights and drinking. It was the swinging 60s, after all - and Japan could evidently swing with the best of them. It feels a lifetime away, another planet, almost. At other moments, the memoir offers more universal, timeless sentiments; a self-affirmation of feelings so many of us will have experienced ourselves, encapsulating that singular 'pull' the country's largest metropolis exerts on the wide-eyed foreigner:

'I was already heavily addicted to Tokyo. I liked the incredible energy, the activity, the politeness, the orderliness, the cleanliness, the efficiency, the trains that always arrived on time, the mix of the old and new, the temples, the shrines, the crowds, the bright neon lights, the charm, and the uniqueness of it all.'

There is no doubt that Whiting's account is unapologetically sentimental and sensational at moments. It looks at Tokyo not so much through rose-tinted glasses - after all, it is highly candid about its seedier side throughout - but through the gaze of one long since converted to its charms; the tight grip of a love affair from which there is no turning back. As Whiting continues to teach English to a succession of Japanese, he quickly discovers that it is invariably he who comes away from the experience having learnt the most, and many of his resultant insights into the Japanese mindset and way of life are vividly regaled. Another memorable anecdote: His local neighbourhood watchperson, who seemingly knows the social comings and goings of everyone, waves cheerily and informs him: ‘You had visitors today,’ - Whiting goes up the stairs to his tiny flat and opens the door to find two of his students have somehow let themselves in, cleaned the place spotlessly, and left him a little cake from the nearby bakery.

As the years march on, we hear Whiting’s thoughts on topics ranging from politics to baseball. Whiting’s passion for the latter is clearly palpable, and even for those with no prior interest in the sport, his enthusiasm is catching - particularly the parallels he draws between the sport and the Zen-like qualities of its samurai spirit. Like many of Whiting’s accounts though, there is often a darker story to tell beneath it all - most anecdotes coming back to the extreme sense of discipline and work ethic ingrained throughout Japanese life. Friends abandon a youth of political activism to ‘grow up’, join society and get married. Workers drink themselves to devastation to cope with the stress of Tokyo salaryman culture. The endless monotony of consensus-generating meetings. Young women hired by banks purely to serve as future wives for the male staff. All are conveyed in compelling detail, and Whiting’s thought process as he tries to negotiate the gap between the America of his birth, and the Japan that he increasingly finds himself assimilating into, are a powerful case study on the emotional realities of prolonged expat living.

One hopes this memoir will find a home alongside other great recollections of 20th century Japan, such as Ian Buruma's A Tokyo Romance or Alex Kerr's Lost Japan. It is so easy for us all to be 'experts' in the nuances of Japanese culture these days, with a wealth of information at our fingerprints via the Internet - but it is for precisely this reason that we owe it to ourselves to cherish accounts of this nature, of the individual, because they present us with an intimacy and trueness of feeling that with every year passes further into the past. These are more than picture postcards of history, or lines in a textbook. Japan changes, evolves, as it must - but the Japan of this book, and Whiting's journey through it, forms part of an account of moments in time that deserve to be remembered. Nation and individual, entangled together - a tale of a life, truly 'lived'.